“Time Is the Most Important Ingredient”: How Antoine Lie Redefines the Role of the Perfumer

Written by Kristina Kybartaite-Damule

Antoine Lie doesn’t just craft perfumes – he challenges conventions, builds formulas around unexpected contrasts, and insists on the recognition of perfumery as a true art form. In an interview for PlezuroMag, he reflects on his creative freedom, artistic vision behind iconic perfumes, and the bold choices that have defined his career.

Antoine Lie / Photos from personal album

For past three decades, Antoine Lie has been one of the most compelling voices in modern perfumery. Trained in the classical tradition but driven by a rebellious spirit, Lie has worked for some of the world’s top fragrance houses, including Givaudan and Takasago. Today, as an independent perfumer and founder of Antoine Lie Olfactive Experience, he enjoys the freedom to pursue creative projects on his own terms.

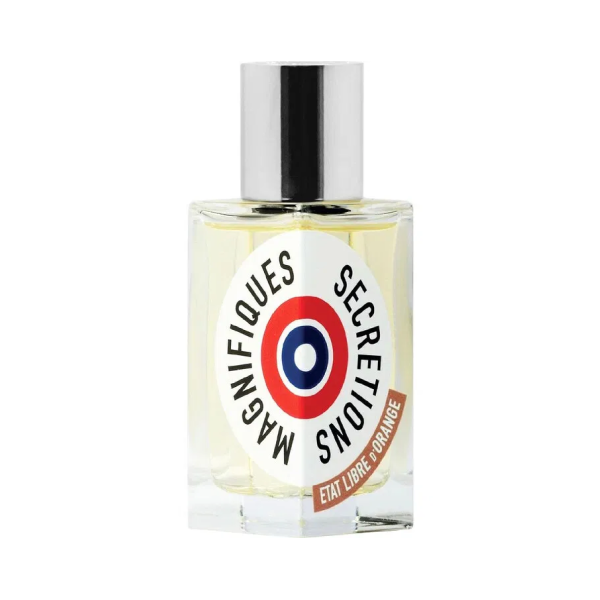

With a portfolio of more than 100 perfumes, his work spans the commercial and the conceptual. He is the nose behind global bestsellers like Versace Crystal Noir and Armani Code, but also behind cult niche creations for Puredistance, Les Indémodables, and Etat Libre d’Orange, where his boundary-pushing fragrance Sécrétions Magnifiques became one of the most talked-about perfumes in recent history.

Despite his success, Lie’s ambition goes far beyond formulas. His dream is to see perfumers recognized as artists in their own right – equal to painters, sculptors, or musicians. "To me, it’s very important,” he says. “I want perfumery to be seen as an art, and perfumers to be respected as the artists they are.”

Dive into our interview with Antoine Lie for PlezuroMag to discover the stories behind his most iconic fragrances, his bold views on the perfume industry, and his visionary quest to elevate the recognition of perfumers.

What is your first scent memory?

Actually, I was really sensitive to smell since a young age. I've got really strong memory of the smells of some of my toys, my teddy bear—even the carpet that I was crawling on when I was really young, or the smell of the leather sofa in the living room. I don't even know if I was walking already. I cannot remember the visual, the environment. So it's very funny that I remember the smell.

And later, I went many times during the weekends to a mountain chain near Strasbourg where I lived, called Les Vosges. It was full of natural smells like earth, woods, grass, some humid vegetation. That's why, I think, the subject of naturality is strong in my fragrances. I love to work with the naturals—dark, earthy, leathery notes—because I used to live in the nature when I was young. When you are really young, you are like a sponge and you're taking in all kinds of information or sensations, and later that's what is leading you.

So maybe if I had lived in another place, I would've loved citrus or flowers. I'm not a lot into flowers, when you think about it—maybe because I was raised in a place where I was not in direct contact with flowers.

Can you tell our readers a little bit about your path? When did you realize that you wanted to be a perfumer, and what steps did you take to become one?

Since I was really sensitive to smell, I was also a nightmare for my mother. I didn't want to eat a dish because it was not smelling the right way for me, even though it was maybe tasting good. Every time I was smelling something!

My mother was also a fragrance lover. I mean, not a fragrance lover like now, like a collector or something, but she used it. In the past, there were not as many fragrances on the market, but, to name a couple, she liked Chanel N°19, Opium. So I had access to these scents, and they are still iconic. I was really attracted by the smells, and I realized that I wanted to know how it was made.

I was not in Grasse, not in contact with any people from the industry. My mother and my father were teachers and they had no idea about the perfume business. So, it was difficult to get information, especially in the '70s–'80s, because it was very secret.

But at some point, I found some articles about fragrances in the press, and I realized that I could be a perfumer—the job of perfumer exists. I thought that maybe I could try to get into some companies where they were making fragrances, to have the opportunity to be trained. But it was not working like that. As I said, it's very secretive and closed to all the other people from outside Grasse and the industry. Somebody told me that I had to take chemistry studies and maybe then I could get into this business, because it's linked to the chemical industry.

So I decided to take chemistry studies, without really liking chemistry. But I knew it was a way to get to what I wanted—although it was wrong and a long, a very long way. So, for years I was learning about chemistry when suddenly I met somebody who told me that I should try to call a company called Roure (now Givaudan). It was a company in Grasse, and they had an internal school where you could be trained. I met those guys and they said, “You know what? It's a good opportunity for you because we really want to open the school to outsiders and not just people that are connected to the families of the business.”

They said that motivation and passion can be interesting for them, and not just the connections. So, I took the school, and this is how I entered the industry.

And once you entered, what surprised you the most in this industry?

I was surprised that it was not a traditional school. It was a very peaceful and quiet classroom because we were only four or five students, picked from around the world to study fragrances and the ingredients.

When I was studying chemistry, it was intense. You get a lot of lessons, you have to study a lot outside the university. Here, it was not at all like this—you had to take your time. It was a great learning process for me as a student because I learned to actually take my time to formulate and to think before making the formula.

I think it also plays a role in the way I like to work now—not like a machine. When you're a perfumer in the big companies, you have so much pressure that you don't have the time to think. You just have the time to mix things very quickly, hoping it'll do something interesting. And that's why I became independent. So I can take the time I want. If I want to get inspired and I need to walk or I need to go to an exhibition, I can take that time. And that's important. I always say that actually one of the most important ingredients in my work, and I think in perfumery in general, is time.

Talking about time – you have been working with designer brands, with big commercial brands, and also with niche houses. Can you compare how much time it takes creating for different companies, and how the work process differs?

Completely. Especially now, after the beginning of the 2000s, because before it was another way of working. When I had just come out of the school and went to Paris to become a junior perfumer, at the time, perfumers were still in direct contact with the brand without too much interference or filtering from marketing, testing, things like that. Which was very interesting because the customer was coming to the office, they were working together, just one or two evaluators. But basically, the dialogue was direct.

Later, it became completely different. Too much money was at stake and the perfumes needed to be profitable right away. They didn't have the time to wait for success, so they wanted to reduce the risks. And so they started doing a lot of testing and things like that.

I started with the old way of developing fragrances and I still thought it was the best way, because it was the most artistic way to do it. Because there was a dialogue between the brand and the perfumers. Of course, they were discussing, balancing, changing, modifying the perfume, but nobody was coming in to say, “Oh, but by the way, your thing is not good for this country or this country, or these people, or that, or this.” That's when the financial system came, to reduce all the risks.

That became completely obsolete. What the perfumer had to say in the fragrance was not respected anymore. And the brands had to just listen to the test consumer and what the marketing would say.

This happened when I had just entered the business in the late eighties–beginning of nineties. And then it moved exponentially to what we have now –now you even get AI. When you are developing a fragrance for big brands, they're doing many different tests, like sniff tests, in-use tests, recall tests – I mean, so many tests! You're working not as an artist, not even as a perfumer anymore – I would say more like a super technician, because you are here to interpret data and analysis from the test consumer and try to change things based on what the panel wants to smell, and not on what the brand wants or what the fragrance needs to be to stand out in the market.

So it's a completely different way of developing things. You are here to win the business at any cost. Basically, you have no say. You, as I said, are the technician and you're here to please the management by winning the project.

Some perfumers, they don't care and they like to work that way, because what is interesting for them is to have their names linked to a big launch, even if it's going to be a flop. And also the money, because after it works, it brings you a good bonus.

But I was not completely satisfied. I was searching for something like what I recalled when I had just started – where you had more dialogue with the brand. And that's when I discovered that some brands—the first niche brands from the early 2000s – were developing things differently, without any testing, any consumer panels, just discussing with the perfumer and allowing him to be very creative and allowing for no limits in terms of price.

That changed the whole thing. I was much more attracted to this kind of perfumery. Even though working for the big groups was elementary in a way, and it helped me to make my living, I had no real pleasure. The real pleasure was in the small business. We found a way that I was still working for the big brands, but they allowed me to work on the small ones too. It was like oxygen for me when I was completely depressed because of what I had to do for the big groups, which was not at all inspiring or motivating or interesting. I was able to work on small projects, and it was very uplifting.

My next question was about why you created Antoine Lie Olfactive Experience, but it seems like you just answered that.

The system is very strange, because even when you're in the business, doing your passion, creating fragrances – I was not really satisfied or happy. The problem is, they treat you like a king in a golden cage. It means that you think you're free, you're treated really well, you have no problems with money or salary – but you cannot say anything. You just have to shut up. You can’t say, “Oh, by the way, I think we should do this.” They will just look at you and say, “You're just a perfumer. You do fragrances, and you stay quiet about management, strategy, and what’s good for the company.” You're not here to say anything, which was, to me, completely wrong.

I think we need many more perfumers at the top level of management to maybe try to change things, but I think it might be too late. It's just the way I personally feel.

That's why I moved from Givaudan to Takasago. I thought that, being a smaller structure, maybe I could work on different things. But it didn’t work – it’s a long story. They fired me.

Then you start thinking, what do I want to do? Do I go back to the big game, which is boring, where you're at the disposal of the big groups? Maybe you don’t want to take the risks? I had a family to feed, so it was difficult to take risks. But when you're forced to take them, you take them. And I was fortunate enough that it worked. Because now I’m really pleased with the way I’m working and what’s happening – it’s just a dream. It’s the best time of my career, in terms of how I work, how I think, and the people I work with – they’re people I actually like. There’s no one toxic around me anymore. No, it’s another story.

Now I can say if I don’t feel a project. If you just want me to copy something? There’s no way I’m going to do it. So I can just say no. I have a lot of freedom right now. That’s a big difference.

Let’s talk about your creations. You’re the author behind one of the most controversial perfumes in the community, Sécrétions Magnifiques. What drew you to this concept, and did you expect it to be as big as it is?

It's a long story, but I’ll try to make it short. It was around the time when État Libre d’Orange had just launched. I met Etienne de Swardt, the founder. At the time, I was completely unhappy with where perfumery was going – it was the early 2000s, with all the testing, marketing, and constant copying. When you were working on big projects for the big groups, the goal was always to please, to make sure your fragrance would be liked by the most people.

Etienne came to me and said, “I want to do a fragrance that’s going to be liked by only five people in the world, and everyone else will reject it. It will be very polarizing.” I thought that was a very artistic position to take – it felt like a rebellion against where the industry was heading.

He wanted to do something that was actually very interesting to me, for another reason I’ll explain.

He said he wanted to create a fragrance inspired by internal fluids – what happens in the body when you're falling in love or making love. It’s difficult to imagine, but it’s true: when you're in love, your heart beats faster, you sweat, there’s saliva, adrenaline – things are happening inside. The idea was to try to express, through smell, what’s going on inside the body. Even if it’s unpleasant to talk about saliva, sperm, blood, sweat – that’s the reality. We’re animals. So basically, it was about revealing what truly happens, what love really is.

And when you show reality, it’s not always pleasant. That’s why we prefer lies. We prefer lies over truth, because the truth can be hard to accept. But that’s why I think this perfume is so powerful. Even people who don’t know the story or the meaning behind it still have strong reactions to it. The meaning of the fragrance was to reveal the beauty of love.

I was very surprised by the reactions people had to it. Comments like: “crazy,” “put him in jail,” “he should be in an asylum,” “how can he make a fragrance like that?”

And then others said: “it’s a masterpiece,” “that’s art.” It was the complete opposite of “oh, that’s nice.” I wanted people to react – either love or hate – and that’s what we achieved. That was the goal: to make art. That’s why I think Sécrétions Magnifiques was one of the first truly artistic perfumes in the industry.

Would you say that you use provocation in your other works as well?

Yeah, especially with État Libre d’Orange. For example, Rien was also a reaction against the industry. Because when you’re creating fragrances for big brands and putting them through testing, there’s a standard panel of ingredients you stick to. You avoid certain notes that could ruin the test results – you don’t use animalic notes, leather, aldehydes, green notes, or orris, because it’s also expensive, and they are polarizing.

So I took a lot of ingredients that were blacklisted from industrial perfumery and used them to create the formula for Rien. It ended up being a huge success. It had massive projection – it really shouted. That was intentional, too, because the perfume was called Rien (“nothing” in French), and I wanted people who wore it to be completely noticed. So when someone asked, “What are you wearing?” they could say, “Nothing.” It was a bit of a joke.

Some of your most exceptional perfumes were created for Puredistance, which I personally adore. Can you tell us a little about working with that house, and what attracted you to it?

I met Jan Ewoud, the founder of Puredistance, when I was at Takasago. Someone who worked there was friends with him and said, “I think you two should meet, because I’m sure you have a lot in common in terms of the philosophy of perfumery and the meaning of developing a fragrance.”

When we met, we immediately noticed we had exactly the same feeling about how fragrances should be developed. Jan Ewoud is a very nice and respectful person. We worked very well together. We understood each other perfectly –there was not one moment of misunderstanding. We speak the same language. I think he’s very sincere and authentic.

That’s the way I like to work with people. As I said, if I don’t like them, I don’t work with them – even if they want to give me a lot of money. And for Jan Ewoud, it’s the same. He has a big brand, but they haven’t raised their prices since 2007. It’s not about expansion or market share. It’s about building a story – a very different kind of brand. A little bit like Les Indémodables, another house I work with. It’s the same feeling, the same approach. Very passionate about fragrance. People come to these brands because they’re different, and because they’re very high quality.

Jan Ewoud was one of the best encounters I’ve had in my career, because he gave me the opportunity to develop such unique fragrances. Of course, he was there to guide me, but he gave me full freedom to choose ingredients and explore. The relationship with Jan Ewoud is outstanding.

Speaking of recent launches—the two Japan-themed perfumes for Maison de L’Asie. Can you tell us about the concept behind them?

Definitely. When Elizabeth Liau, the founder of the brand, contacted me, she asked me to develop two fragrances inspired by Japan. She wanted me to work in the way I’m pretty known for – creating contrasted fragrances, putting together ingredients that are not obviously meant to be blended. Sometimes it’s interesting to do that precisely because of the contrast, even if it might be surprising or not as harmonious as people might expect.

She wanted me to reveal Japan. But you know, Japan is a very strange country – I know it quite well. People are very sad, calm, quiet, but it’s also one of the most violent societies in some ways. For instanse, Japanese cinema – there’s a lot of blood, swords, very intense, even going back to the time of the Samurai. On one side, there’s a deeply traditional lifestyle, a lot of respect for the older generation. On the other, the younger generation is completely crazy – colorful dresses and socks, dressing like some characters I don’t even know because I’m too old.

So she wanted me to develop two fragrances based on those contrasts.

One is called L’Ibasho. The idea was to mix two types of powder – gunpowder and rice powder. It’s a kind of revelation of life and death, in a way. The gunpowder symbolizes violence and death, while the rice powder – like the cosmetic powder geishas used – represents beauty, life, and joy.

The other one is Guns of Sakura, with the cherry blossom. For me, it’s very poetic, very delicate. I had to create a specific accord for it. It’s more innocent, more feminine, more powdery and fluid. There’s not much contrast in this fragrance, but it’s meant to be compared with the other one, which is more violent.

Is there a project you still dream of doing?

I want perfumers to be recognized as artists, and I want perfumery to be seen as an art form. If your work is displayed in a museum, then you can be classified as an artist. So the project would be to release a fragrance – or a smell, or a concept – that involves perfumery and another art form. Maybe working with a sculptor, a painter… Something that allows perfumery to enter the museum space. Then, you're officially labeled as an artist.

To me, that’s very important, because I feel there’s still a lack of respect. I mean, I have that respect because I say it out loud, and I work freely, like an artist. But many others don’t receive any royalties for what they create.

So yes, that’s the dream project – to bring real respect to perfumers and have them recognized as artists.

Thank you for your time.

Related articles:

Jan Ewoud Vos and the World of Puredistance: a Different Way to Create Timeless Beauty